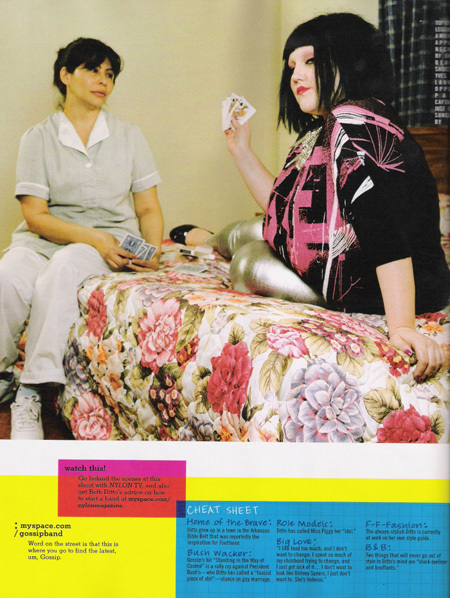

While the Gossip isn't in my regular rotation (there's always something about the production value of their albums that throws me), Beth Ditto's ascension as a fearlessly fat and femme style icon is on my radar for sure. There's much to be said about Beth Ditto, fat and fashion, but the above photograph from Ditto's eight-page editorial in NYLON's recent music issue is about none of these things for me.

It's about the woman who may or may not be a real housekeeper at the motel at which this editorial was photographed, sitting on the edge of the bed with a handful of cards and gazing at Ditto with a weary but guarded expression. In the story that coalesces for me, studying this photograph, she has just been forced to play cards with a guest -- not because she wants to, but because she could lose her job if she doesn't. Nor does the game even feel like a break from her domestic labor; this sort of affective labor is no less taxing. In her mind (in the story I imagine about this editorial), she calculates how much longer she'll have to stay and clean in order to meet her day's quota.

But none of this is supposed to be visible (or even viable) in the photograph. We are not meant to consider her story. (And I'm made uncomfortable by my own attempt to "give" her an interior life.) Instead, the woman of color in her drab housekeeper's uniform is simply another part of the furnishing in this bland motel room. She is banished as mere and muted background, the better to illuminate Ditto's extraordinary excess of shine and glamor. For that reason, this editorial photograph both angers and saddens me.

Much has been written about the uses of people of color as part of the landscape in fashion editorials. (See, for just a small sample, Make Fetch Happen's disgust for colonial chic, Racialicious' archive on fashion, or bell hooks' canonical essay "Eating the Other"). This cliché includes "exotic" locales and touristic images of the "natives," who wear clothes and other adornment that are imagined as traditional and time-bound. (In Viet Nam, a frequent setting, these might be so-called pajamas and conical hats; in the often-undifferentiated Africa, also a regular landscape, loincloths and face paint). The deliberate contrast between these figures (native and model) is arranged along a spectrum of race, but also time and space. The Vietnamese, the African, the Peruvian, are imagined to live at a temporal and geographic distance from the modern, and implicitly Western, woman who might wear these fashionable clothes. The compulsion to return to this scene, through which the natives in their deindividuating garb serve to highlight the cosmopolitanism, the expressive and unique sense of self, of the woman who wears (or at least covets) Prada, reveals much about the continuing investments of fashionable discourses to an inheritance of colonial regimes of power and knowledge. It is a fantasy, yes, but no less powerful for being so.

What is happening here is no less committed to this uneven distribution. The uniform deindividuates the housekeeper as much as a generic “native” costume might; she blends nearly seamlessly into the walls of the motel room, she clashes dully with the bedspread. We might even argue that the uniform in fact becomes the generic “native” costume; the racialization of this (also feminized) domestic labor in the hospitality industry has already been normalized, naturalized, to make this premise utterly reasonable. The housekeeper is meant to be invisible, working unobtrusively around the perceptual periphery of the guest, and this scene is no exception. She is part of the set dressing, in which Ditto’s bright and hard-edged New Wave styling intrudes to asserts itself as distinct, as foreground. This blandness, this generic and ordinary landscape, the photograph suggests, is not Ditto's natural habitat. By implication, it is the housekeeper's.

And although Ditto and the housekeeper more obviously inhabit the same historical moment, they do not exist in the same tempo. The housekeeper’s time is syncopated, regulated, by her repetitive labor; as imagined here, Ditto’s time, perhaps filled with boredom in search of novelty (like consorting with the housekeeper), stretches out at leisure. Here, the temporal distance is a matter of how each person experiences this small interval, this interlude of a card game.

Meanwhile Ditto addresses the camera with a sexy, sly look that feels intimate, insider-y. This sort of winking acknowledgment of the viewer is important to the style sensibility that NYLON cultivates as an "alternative" fashion magazine. The NYLON reader is interpellated as fashion-forward, “in the know,” someone who can “get” and appreciate the many cultural references to MisShapes, Cobrasnake, Cory Kennedy, Williamsburg, whatever. (And, it should be noted, the world of NYLON is glaringly white.) But it also reinforces the distance between the presumed viewer and the housekeeper who is not included in this wink, and who is not imagined to share this same base of knowledge. (It doesn't seem to matter whether Ditto's look is conspiratorial --"Isn't it fun to be fabulous?"-- or self-deprecating --"Isn't this fashionable life total bullshit?"-- because this insight is decidedly not shared with the housekeeper.) And, of course, as Foucault taught us, knowledge is inextricably caught up in power – and this one photograph encapsulates this bind, how even this “minor” event, the trivial detail of the housekeeper's uniform or Ditto’s look, might be complicit.

In a million ways, the housekeeper's inclusion in this image emphasizes, and even enacts, her exclusion. I would have enjoyed this editorial much, much more, had she not been made to appear in it for the purpose of disappearing her all the better.

EDIT: For updates and further thoughts, see Background Color, Redux and Background Color, Redux II.

8 comments:

This post is so dead-on. Thank you for writing it.

Thanks for this post, Mimi! Looking at Beth Ditto's face, I also wonder if it's completely accidental that she's performing a certain westernised "geisha" look, blunt fringe, paler than pale base, red bow mouth, etc. It feels to me as if that's part of the racial economy of appropriation at work here. -- I mean, it's probably coincidental in the context of the photo shoot, but no accident that two very different forms of cultural appropriation of "Asian femininity" are happening at the same time, both working to produce Ditto as glamorous and retaining the [white] power to appropriate the iconography of difference.

not to mention the "asian" elements of beth ditto's getup.

Really this is a fantastic post. Thank you for publishing it.

ditto's racialized make-up didn't escape me either. your whole post is dead-on.

So much problematic behavior in one photo I don't even know where to start. Thank you for this post. Thank you for taking the time to write what feels like a call for folks in the SA/FA movement to put up or shut the fuck up.

This photo is an example of what woc are talking about when we discuss the ways in which various activist spaces are invalidating and alienating.

i want to speak the way you write. and i want to marry you. except i don't believe in marriage. but i believe in your knowledge/power to blow my fuckin mind

Can I just say that there are POC's in the FA movement if you don't mind, although I must say I have many qualms regarding the assumptions, orientation and opinions expressed in FA. I still think that participation is justified and I would suggest there is still opportunity in the fact that this tranch of it is still new.

Secondly I have to say that a lot of your analysis hit the spot, I barely noticed the room attendant(?)- yeah, I know.

Although that was as much because I was immediately arrested by BD's make-up, I was engaged by how I felt about that.

Where I differ is that I think that the central issue here is class, would it have made any essential difference if the other lady was white and BD was a WOC?

Post a Comment