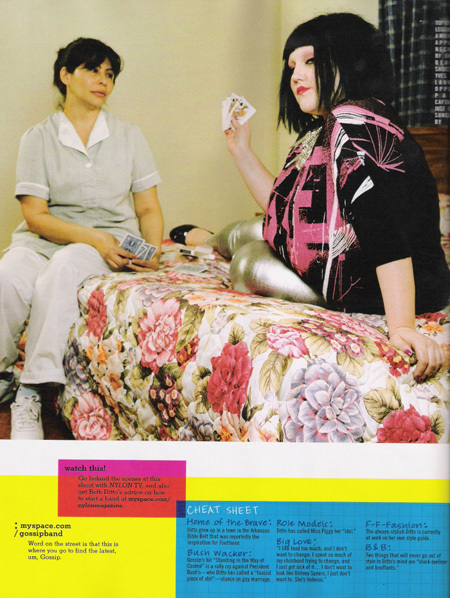

Fig. 1

First, let me mention that I will reject comments that are insulting or poorly composed. (Phrases strung together in a jumble connected with ellipses are not fun to read.) Second, the author of the rejected comment does point out something worth noting -- yes, the editorial certainly does reference a canonical theme in European art history, and no, this hardly excuses the editorial. If anything, it makes the editorial that much more a poignant example of the long duration of racisms and their entanglements with other vectors of power, including gender, sexuality, empire and labor. That is, what this comparison makes too obvious is that colonial and imperial histories of conquest and aesthetics continue to exert themselves in the present.

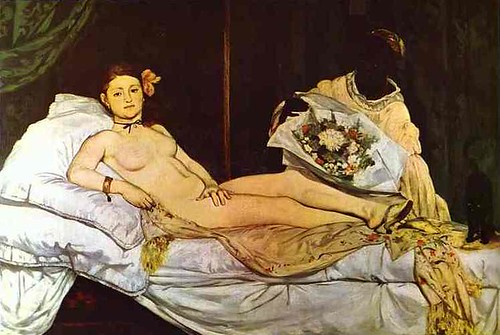

Fig. 2

In an essay called Slavery is a Woman, art historian James Smalls writes of this genre: "A recognized example of the standard representation of blacks in European art is provided by Jean-Marc Nattier's 1733 Mademoiselle de Clermont at Her Bath Attended by Slaves. (Fig. 2) There, black women are shown in their expected roles as servants and exoticized complements to the white mistress. [...] The portrait constitutes a visual record of white woman's construction and affirmation of self through the racial and cultural Other. [...] The black woman's headwrap and partial nudity are signs that mark her as different from white womanhood. As well, they constitute visible markers of white woman's command over black woman's labor." (The whole essay -- a meditation on visual representations of black women in 19th century European portraiture-- is well worth a look.)

And in an American Literature essay about an African American experimentalist poet, Deborah Mix speaks about these hauntingly familiar images too (to contextualize one of Harryette Mullen's poems, "A Petticoat"):

Questions of power—to speak, to create, to relax—are further interrogated by the fact that one woman lounges while another hovers inattendance. [...] In signifying on ‘‘A Petticoat , ’’ Mullen evokes Édouard Manet’s painting Olympia, whose nude, reclining white woman gazes directly at the viewer, while a black woman in a shapeless pink dress hovers in the background. Feminist art historians have read Manet’s painting as representing transgressive female sexuality, its female nude bold enough not only to revel in her nudity but also to stare directly at her would-be voyeurs. But this boldness appears to be available only to the upper- class white woman; the black servant nearly disappears into the shadows, holding flowers that may be a lover’s gift to Olympia. The servant’s sexuality, even her identity, appears to be subordinated to her mistress’s sexual power and to the power of the gaze. (Both Olympia and her viewers are free to look brazenly, but the black woman is not.) In fact, the black woman’s ill-fitting dress may have been a gift from her mistress, an exchange in which white femininity is thrust upon a black woman as both condescending generosity and an assertion of authority. Yet the dress, and the attitudes about gender and racial identity for which it is synecdoche, fails to fit. Furthermore, as the white woman luxuriates in the "rosy charms" of her pink nudity, the dark-skinned maid "wears [the white woman’s] color." Still cloaked in traditional "pink and white," the servant apparently exists to complement the privilege of Olympia’s femininity and sexuality. Olympia and her couch are painted on top of the murky background of heavy draperies and, of course, her servant, whose presence is highlighted primarily through the dress she wears rather than through her own body. In interpreting Mullen’s insertion of the Manet painting into her re-vision of [Gertrude] Stein’s poem, we confront the ways in which Stein, like "Olympia," enjoyed privileges conferred by her class and race. Stein’s boldness as a writer was enabled by wealth and leisure; those who enabled that leisure, such as domestic workers, are rendered nearly invisible.

The conditions of possibility for what the NYLON editorial looks like today are deeply embedded in the now-blunt nature of these earlier images. It might be a project for another time to attend to what has and has not changed about these aesthetic formations, their structures of knowledge production (especially of racial thinking), and unexpected entailments, but for now, I think it's clear that the aesthetic conventions of the NYLON editorial are both jarringly new and disturbingly the same.