This is, of course, the rehearsal of what Walter Benjamin called “the aura” in his essay, “The Work of Art in an Age of Mechanical Reproduction. This "aura," he argued, was first derived from art's original value in religious ceremonies and rituals, and later from the Renaissance's secularization of art as singular works of individual genius. This produced the notion of "art of art's sake," of art as transcendent and of the artist guided by a privileged insight into capital-T truth, in the 1800s, against the rapid industrialization and urbanization of "culture."

We can see this at work in claims by major designers against Forever 21 and its cheap cohort of retailers. At the same time, major designers buying vintage and copying these pieces include Jill Stuart, Anna Sui, Jean Paul Gautier, and of course Marc Jacobs, who is seen browsing vintage stores in New York City for just this purpose in his new documentary. Some of these same designers are part of copyright lawsuits against Forever 21 and other discount retailers – and a few are finding themselves at the other end of such lawsuits.

Famed Belgian deconstructionist designer Martin Margiela was recently dinged for only slightly, --very, very slightly-- modifying a copyrighted t-shirt design featuring an ominous sky full of thundering white horses and a barren mountain cliff. Reproduced on an asymmetrically draped and padded cotton shirt, and sold out at the designer’s Beverly Hills boutique, the almost exact image’s copyright belongs to British artist David Penfound, who sells reproduction rights to the painting for as much as one of Margiela’s shirts.

TOP: Margiela's version from the S/S 08 collection, BOTTOM: Penfound's original from a $20 t-shirt.

Margiela's representatives say the graphic is a "collage of nostalgic images compiled in-house." Nevermind for a moment that there is pretty much no "collage" effect at all in the copy. This invocation of nostalgia is telling because it suggests a fashion-backwardness, a temporal anomaly, brought forward into the future at the behest of the fashion-forward. This nostalgia for a certain set of images, however, is nonetheless contemporaneous; a particular aesthetic imagined to be still alive and, as many observers have noted, representative of a series of degraded cultural touchstones: “Midwestern gas station,” “trailer trash,” and “cheap and ugly souvenir.” (This chain of associations is no accident.) One fashion blog commentator wrote, “I picture the original on someone buying an extra-large order of nachos and a foot-long hot dog.“

These aesthetic judgments of the original design are called upon in both defenses and denunciations of Margiela. In the first, such judgments suggest that the original design was of such poor aesthetic quality that Margiela’s replication of the design only elevated something that was otherwise cultural detritus. Which is to say, Margiela’s transformation of the design (in the details and drape) can and should be regarded as the design’s alienation –not as isolation but as repudiation—of the original. In the second, such judgments argue that the original design is too ugly to redeem, too “cheesy” to rip off.

So what sort of aura is it when major designers copy cheap and derided --in no uncertain terms of economic and cultural capital— thrift store and vintage items? How are discourses of art and originality distributed unevenly, unequally, here? How do certain ideas about other peoples’ styles travel, and inform (or not!) the clothing options and choices for the consumers of these styles? How do these same ideas inform the clothing options and choices for consumers of these styles when they are “transformed” in other contexts – whether Urban Outfitters’s array of vintage reprints for the college crowd, or Martin Margiela’s vintage rip off for the wealthy?

Consider feminist media theorist Judith Williamson’s seminal essay, “No Woman Is an Island:” "It is currently 'in' for the young and well-fed to go around in torn rags, but not for tramps to do so. In other words, the appropriation of other people's dress is fashionable provided it is perfectly clear that you are, in fact, different from whoever would normally wear such clothes." Written in 1986, it seems this still applies.

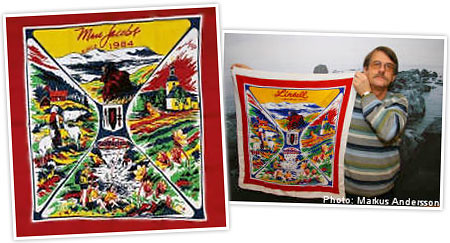

Meanwhile, 55 year-old Swede, Göran Olofsson, has been compensated an unknown amount for the scarf that Marc Jacobs blatantly plagiarized for Louis Vuitton. The scarf had been designed and created by Olofsson’s father Gosta in the 1950s as part of a line of tourist souvenirs for the Swedish small town of Linsell, and the print on Jacob's silk scarf was a near exact copy. (He replaced the name of the town with the tagline, "Marc Jacobs since 1984.") (Mimi)

No comments:

Post a Comment