I just watched Daphne Guinness’ short film “Phenomenology of Body” which premiered on New York Times T Magazine today. Something of a misnomer, “Phenomenology of Body” doesn’t offer a discussion of bodies but rather a broad survey of archetypal women identifiable by her mode of dress or undress, as is the case with Eve and her terribly trite fig leaf. Each celebrated female figure is rotated in and out in rough chronological order—Eve to Joan of Arc to Marie Antoinette and so on. (There’s definitely a Leni Riefenstahl-esque quality to Guinness’ work.) The film’s dramatic end is a Muslim woman in a red burqa who unveils herself. In the feminist logic of the film, this unveiling is necessary so that she can be included in this Western imagined history of women and fashion.

In a Women’s Wear Daily article, Guinness has this to say about her film: “It’s about the body and the soul, concealing and revealing, empowerment; clothing has always been so political. The message is that we all have the power to choose.”

Mimi and I have been working on companion essays that examine the discursive and ideological operations of fashion and beauty in an age of terrorism. I won’t rehearse our entire arguments here—we’ll let you know when/where the papers are published!—but I do want to say that Guinness’ description eerily echoes the mission statements of other programs and campaigns of “empowerment” that aim to unveil Muslim women and democratize fashion for middle and working class American women by linking fashion and beauty to the language of human rights and civil rights. (I hope Mimi will expand on this in a later post or in the comments!) Of course, “empowerment,” as we see in “Phenomenology of Body,” is wielded in patronizing and imperialist ways that suggest the masses of unfashionably oppressed and oppressively unfashionable women are in need of saving.

27 June 2008

19 June 2008

LINKAGE: Racialicious

I only recently discovered Racialicious, a whip-smart blog about he intersection of race and popular culture, and wanted to link some of their posts on fashion.

A Case for Hipsters (of Color) suggests that the whitewashing of the hipster figure loses a history of people of color in experimental or avant-garde scenes.

The Stereotype of the Middle Eastern Label Whore tackles the portrayal of Middle Eastern women as lacking taste, style, or any rational ability to discern the two.

Another look at Muslim women in fashion news that deconstructs the desire to see what might lie "beneath the veil" (especially if it's sexy).

Ghetto Chic, to Wear or Not to Wear examines the popularization of certain items of ghetto chic (e.g., door-knockers, nameplate necklaces) and the loss of their historical significance in the process.

Liya Kebede's Vogue editorial set in Mali sparks some important questions about shoots that feature "exotic" locations and locals.

A Case for Hipsters (of Color) suggests that the whitewashing of the hipster figure loses a history of people of color in experimental or avant-garde scenes.

The Stereotype of the Middle Eastern Label Whore tackles the portrayal of Middle Eastern women as lacking taste, style, or any rational ability to discern the two.

Another look at Muslim women in fashion news that deconstructs the desire to see what might lie "beneath the veil" (especially if it's sexy).

Ghetto Chic, to Wear or Not to Wear examines the popularization of certain items of ghetto chic (e.g., door-knockers, nameplate necklaces) and the loss of their historical significance in the process.

Liya Kebede's Vogue editorial set in Mali sparks some important questions about shoots that feature "exotic" locations and locals.

Black Is The New Black

The July Vogue Italia should be arriving on American shores in the next few weeks, and of course New York Times' Cathy Horyn has a sneak peak of, as well as interviews with, some of the models who appear in the “historic” issue. (For the Thursday Fashion and Style section, she also penned an essay called "Conspicuous By Their Presence.") Her column and the comments posted to it include some interesting, and some troubling, insights. Reading these, I want to post some initial thoughts:

1. A commentator noted: "I’m very excited about the Italian Vogue issue, but I also think we need to remember this isn’t the first time an all black issue has appeared on the news stands. An 'all black issue' is not necessarily an innovation or groundbreaking within the context of fashion publishing, so much as it is a rarity. After all most magazines out there are typically 'all-white' issues, while a magazine like Essence has always been 'all-black,' but we don’t make a fuss about those."

I think that’s critically important here. Vogue is a gatekeeper in the industry, so it’s important that its publication of an all-black issue be located in just this power to arbitrate what counts as fashionable, as beautiful. For all these reasons it’s also important to ask about what anthropologist Arjun Appadurai calls “the traffic in criteria:” By what criteria does Vogue’s publication of this issue count as “historic” or “groundbreaking”? What does it mean that black aesthetic and commercial practices, such as the rise of magazines like Essence or Jet and their critical importance to the cultivation of black models in the 1950s, are corralled under a different set of criteria?

2. In an e-mail from stylist Edward Enniful on the Steven Meisel shoot with Naomi Campbell, he wrote: "We laughed, ribbed each other, and talked about the old days, but most of all we created a story that reflected black dreams and aspirations. There was no hip-hop gangsterism, no ghetto fabulousness, no bling-bling clichés." Without choosing one sort of fabulousness over another, I think it’s fascinating how contemporary black expressive subcultures –which, let’s face it, have also become global commodities and art forms on a massive scale-- are somehow not located as a site for “black dreams and aspirations” in this statement.

This rhetorical maneuver seems to be happening on two levels. The first implies that hip-hop is either a site for only inappropriate black dreams and aspirations, or that the dreams and aspirations so often expressed through hip-hop are dead ends. The second positions "hip-hop gangsterism, ghetto fabulousness, and bling-bling clichés" in opposition to a presumably more universal standard of glamour, which is imagined to be clearly, discernibly, the proper location of black dreams, et cetera. (And also, by the way, reduces hip-hop to a single dimension.) This standard, however, has never been all that universal– as evidenced by the heralding of this issue as historic, not because it’s the first ever all-black issue of a fashion magazine, but because it’s the first ever all-black issue of Vogue.

What interests me about these qualities and values we bandy about –style, fashion, glamour, beauty, sophistication, excellence —is their histories. There’s a reason why ghetto fabulousness names both a particular moment for certain (not all) black aesthetic practices and a particular site for their emergence. I think it’s important to acknowledge that in doing so, ghetto fabulousness can manifest a complex and complicitous critique of the hierarchies of differential value (aesthetic and socioeconomic) attached to certain bodies, clothes, accessories, et cetera. These hierarchies are deeply embedded in political, economic, and geographic conditions (deindustrialization, urban underdevelopment, white flight, zoning laws, redlining) and racist discourses (blackness as particular rather than universal, blackness as criminal rather than aspirational). The negative discourse about ghetto fabulousness as a sort of false consciousness, a delusion of superficial glamour, a distinct lack of rational economic or "educated" aesthetic sensibilities, a pretense of living large by black and poor persons who are living beyond their means (as if most Americans aren’t doing so!), is a direct descendant of the Reagan era’s stereotype of the welfare queen collecting checks and cruising in her Cadillac. As such, it bears recognizing that all the judgments of taste, "rational" or "irrational" decision-making, and beauty invoked in negative uses of the term ghetto fabulous are deeply ideological and contentious.

This is not an argument that all images of black aesthetics have to be located in hip-hop or urban spaces (which would be totally problematic because African diasporic aesthetics vary so widely), but an argument for being thoughtful about the uneven distribution of what counts as beautiful --and what is defined as ugly in counterpoint-- and why.

3. I’m excited to see Toccara from America’s Next Top Model in the issue! She was done wrong by the show.

1. A commentator noted: "I’m very excited about the Italian Vogue issue, but I also think we need to remember this isn’t the first time an all black issue has appeared on the news stands. An 'all black issue' is not necessarily an innovation or groundbreaking within the context of fashion publishing, so much as it is a rarity. After all most magazines out there are typically 'all-white' issues, while a magazine like Essence has always been 'all-black,' but we don’t make a fuss about those."

I think that’s critically important here. Vogue is a gatekeeper in the industry, so it’s important that its publication of an all-black issue be located in just this power to arbitrate what counts as fashionable, as beautiful. For all these reasons it’s also important to ask about what anthropologist Arjun Appadurai calls “the traffic in criteria:” By what criteria does Vogue’s publication of this issue count as “historic” or “groundbreaking”? What does it mean that black aesthetic and commercial practices, such as the rise of magazines like Essence or Jet and their critical importance to the cultivation of black models in the 1950s, are corralled under a different set of criteria?

2. In an e-mail from stylist Edward Enniful on the Steven Meisel shoot with Naomi Campbell, he wrote: "We laughed, ribbed each other, and talked about the old days, but most of all we created a story that reflected black dreams and aspirations. There was no hip-hop gangsterism, no ghetto fabulousness, no bling-bling clichés." Without choosing one sort of fabulousness over another, I think it’s fascinating how contemporary black expressive subcultures –which, let’s face it, have also become global commodities and art forms on a massive scale-- are somehow not located as a site for “black dreams and aspirations” in this statement.

This rhetorical maneuver seems to be happening on two levels. The first implies that hip-hop is either a site for only inappropriate black dreams and aspirations, or that the dreams and aspirations so often expressed through hip-hop are dead ends. The second positions "hip-hop gangsterism, ghetto fabulousness, and bling-bling clichés" in opposition to a presumably more universal standard of glamour, which is imagined to be clearly, discernibly, the proper location of black dreams, et cetera. (And also, by the way, reduces hip-hop to a single dimension.) This standard, however, has never been all that universal– as evidenced by the heralding of this issue as historic, not because it’s the first ever all-black issue of a fashion magazine, but because it’s the first ever all-black issue of Vogue.

What interests me about these qualities and values we bandy about –style, fashion, glamour, beauty, sophistication, excellence —is their histories. There’s a reason why ghetto fabulousness names both a particular moment for certain (not all) black aesthetic practices and a particular site for their emergence. I think it’s important to acknowledge that in doing so, ghetto fabulousness can manifest a complex and complicitous critique of the hierarchies of differential value (aesthetic and socioeconomic) attached to certain bodies, clothes, accessories, et cetera. These hierarchies are deeply embedded in political, economic, and geographic conditions (deindustrialization, urban underdevelopment, white flight, zoning laws, redlining) and racist discourses (blackness as particular rather than universal, blackness as criminal rather than aspirational). The negative discourse about ghetto fabulousness as a sort of false consciousness, a delusion of superficial glamour, a distinct lack of rational economic or "educated" aesthetic sensibilities, a pretense of living large by black and poor persons who are living beyond their means (as if most Americans aren’t doing so!), is a direct descendant of the Reagan era’s stereotype of the welfare queen collecting checks and cruising in her Cadillac. As such, it bears recognizing that all the judgments of taste, "rational" or "irrational" decision-making, and beauty invoked in negative uses of the term ghetto fabulous are deeply ideological and contentious.

This is not an argument that all images of black aesthetics have to be located in hip-hop or urban spaces (which would be totally problematic because African diasporic aesthetics vary so widely), but an argument for being thoughtful about the uneven distribution of what counts as beautiful --and what is defined as ugly in counterpoint-- and why.

3. I’m excited to see Toccara from America’s Next Top Model in the issue! She was done wrong by the show.

18 June 2008

DESIGNER: Christian Joy

Speaking of classroom style, I would (if I could) wear Christian Joy's stage costumes to lecture. Students wouldn't be able to keep their eyes off me as I outlined the foundations for feminist cultural studies, or described how to put together their reading presentations! Although I admit I was a little mortified when I ran into one of my undergraduate students at the cafe the other day -- I was wearing a thrifted black-and-white cheetah print jumpsuit with a red skinny belt and red flats. Eep! I think it's okay, because she had taken my fashion course (and received a big fat A!) and was herself dressed like an extra from the lesbian cult film Personal Best.

Maybe I'll have to settle for some of the items from Spring collection, as modeled by Karen O from the Yeah Yeah Yeahs?

All images from Christian Joy, of course.

Sweatin'

So it appears that PINK asses will become even more ubiquitous on college campuses, with Victoria's Secret partnering with The Collegiate Licensing Company to launch “exclusive” co-branded merchandise. Victoria’s Secret’s PINK's brand iconography and the names and logos of any one of thirty-three universities –most of them public or land-grant universities— will be paired on their apparel. Already, my campus is awash with Victoria’s Secret sweatpants (either paired with Uggs --really? still?-- or flip-flops), which I didn’t even recognize as such until just a few months ago. (I thought the PINK thing was a breast cancer awareness gimmick.) Sartorially, I’m not looking forward to the proliferation of these decorated with the university logo. But sweatpants are a part of the first set of lessons I teach in my fashion course.

Back in my youth, I’m pretty certain that athletes would wear sweatpants to class but no one else did, really (sweatshirts, yes). Meanwhile, I wore dirty black jeans (we called them “vegan leather” because, after a while, all that dirt and grease would turn the denim shiny) and black t-shirts everyday because I was anti-fashion, but that’s another story (up the punx!). And the spread of sweatpants as casual undergraduate apparel escaped my notice as a graduate student at Berkeley (although I have a great story about the time I was in the library cafe and I saw two undergraduates engaged in oral sex --IN THE CROWDED CAFE-- in matching sweats). In the courses I worked for (gender and women’s studies), I didn’t much see a representative cross-section of the campus population. It’s only since I moved to the Midwest that I’ve had daily exposure to the phenomenon of sweats in the classroom, and I’ve been trying to puzzle it out ever since.

My colleagues express a lot of disgust for the sweatpants brigade, and on a purely aesthetic level, I would rather stab myself in the eye than wear PINK, or anything else in sweatpants form, on my ass. They correlate what appears to be a lazy, unserious approach to classroom appearance with a lazy, unserious approach to classroom performance. Or, more generously, they see the spread of sweats as casual collegiate wear as one manifestation of the pressure to appear “not too smart,” to dumb it down in order to fit the campus climate. Without necessarily deciding that any of these explanations is the “right” one, it does interest me that the language in which we praise or denounce clothing is also the language with which we make moral judgments: right, correct, good, unacceptable, faultless, shabby, threadbare, botched, sloppy, careless. (And I’m sure that the students do the same thing to us – if we also showed up in sweats, they’d surely decide that we were lazy and unserious. I'm amazed that it rarely occurs to them that it's a two-way street.)

I try to set aside my sartorial dislike when I discuss sweatpants with my students, though. And because so many of them wear sweatpants, I ask them why. (I try to keep the “eww” out of my voice when I do.) Some claim that "comfort" is their number one priority, but I push them to consider whether comfort is really such an obvious utilitarian value, or is there more to this idea than meets the eye? What is the content of comfort as a measure? Is it physical, emotional, or social, or some combination of these? What kinds of sweatpants count as comfortable ones? No one is wearing, say, their grandma’s tapered and relaxed-seat sweatpants, which I imagine are physically comfortable but might be socially uncomfortable. No one (so far) has copped to being an adherent to the Grey Sweatsuit Revolution, a semi-ironic art practice that parodies the fashion system as well as the anti-fashion response in its push to create a new fashion/anti-fashion uniform. (From their mission statement: "The grey sweatsuit is our Trojan horse. We create a street trend, a visible statement, the system co-opts it without understanding it’s significance and then... BAM! Grey sweatsuits all up in the area! Our symbolism spreads like anthrax across the anorexic bodies of fashionistas everywhere! They look frantically for the next trend but there is nothing. Only grey sweatsuits.") So some decisions are being made to convey a certain sense of self, via the sweatpants. At that point, someone might speculate that some girls wear sweatpants and painstakingly messy ponytails as a calculated flirtation: “This is what I look like when I’ve just gotten out of bed,” or that some others (boys and girls) are presenting an image of careless youth: “Whatever, it’s all good. Let's do a bar crawl!” We talk then about “spheres” of fashionableness, how the college campus produces its own set of sartorial standards and what might be behind those standards – university personalities (e.g., Ivy League versus Big Ten), ideas about what it means to be a certain type of student, practices of differentiation as well as assimilation, and so on.

A part of what I’m trying to do is get them to acknowledge that broader implications are attached through social and cultural discourses to the clothes we wear, or the clothes others wear; that often the “messages” we think we are presenting about ourselves, about our concerns, are ambiguous, and ideologically loaded whether we are conscious of this or not; and that these messages are being conveyed along axes of often uneven power. For instance, when professors read their appearance as indicative of intellectual laziness, or when university staff recognize students by their sweats, and fellow workers by their absence. I’m also hoping to have them think consciously about the reasons they wear the clothes they do – that “comfort” and the desire to seem effortless, or alternately studious (part of a “I’ve been at the library all day” look), are not necessarily obvious values or qualities but are actively constructed and circulated by their everyday dress practices.

I still hate their sweatpants, though.

Back in my youth, I’m pretty certain that athletes would wear sweatpants to class but no one else did, really (sweatshirts, yes). Meanwhile, I wore dirty black jeans (we called them “vegan leather” because, after a while, all that dirt and grease would turn the denim shiny) and black t-shirts everyday because I was anti-fashion, but that’s another story (up the punx!). And the spread of sweatpants as casual undergraduate apparel escaped my notice as a graduate student at Berkeley (although I have a great story about the time I was in the library cafe and I saw two undergraduates engaged in oral sex --IN THE CROWDED CAFE-- in matching sweats). In the courses I worked for (gender and women’s studies), I didn’t much see a representative cross-section of the campus population. It’s only since I moved to the Midwest that I’ve had daily exposure to the phenomenon of sweats in the classroom, and I’ve been trying to puzzle it out ever since.

My colleagues express a lot of disgust for the sweatpants brigade, and on a purely aesthetic level, I would rather stab myself in the eye than wear PINK, or anything else in sweatpants form, on my ass. They correlate what appears to be a lazy, unserious approach to classroom appearance with a lazy, unserious approach to classroom performance. Or, more generously, they see the spread of sweats as casual collegiate wear as one manifestation of the pressure to appear “not too smart,” to dumb it down in order to fit the campus climate. Without necessarily deciding that any of these explanations is the “right” one, it does interest me that the language in which we praise or denounce clothing is also the language with which we make moral judgments: right, correct, good, unacceptable, faultless, shabby, threadbare, botched, sloppy, careless. (And I’m sure that the students do the same thing to us – if we also showed up in sweats, they’d surely decide that we were lazy and unserious. I'm amazed that it rarely occurs to them that it's a two-way street.)

I try to set aside my sartorial dislike when I discuss sweatpants with my students, though. And because so many of them wear sweatpants, I ask them why. (I try to keep the “eww” out of my voice when I do.) Some claim that "comfort" is their number one priority, but I push them to consider whether comfort is really such an obvious utilitarian value, or is there more to this idea than meets the eye? What is the content of comfort as a measure? Is it physical, emotional, or social, or some combination of these? What kinds of sweatpants count as comfortable ones? No one is wearing, say, their grandma’s tapered and relaxed-seat sweatpants, which I imagine are physically comfortable but might be socially uncomfortable. No one (so far) has copped to being an adherent to the Grey Sweatsuit Revolution, a semi-ironic art practice that parodies the fashion system as well as the anti-fashion response in its push to create a new fashion/anti-fashion uniform. (From their mission statement: "The grey sweatsuit is our Trojan horse. We create a street trend, a visible statement, the system co-opts it without understanding it’s significance and then... BAM! Grey sweatsuits all up in the area! Our symbolism spreads like anthrax across the anorexic bodies of fashionistas everywhere! They look frantically for the next trend but there is nothing. Only grey sweatsuits.") So some decisions are being made to convey a certain sense of self, via the sweatpants. At that point, someone might speculate that some girls wear sweatpants and painstakingly messy ponytails as a calculated flirtation: “This is what I look like when I’ve just gotten out of bed,” or that some others (boys and girls) are presenting an image of careless youth: “Whatever, it’s all good. Let's do a bar crawl!” We talk then about “spheres” of fashionableness, how the college campus produces its own set of sartorial standards and what might be behind those standards – university personalities (e.g., Ivy League versus Big Ten), ideas about what it means to be a certain type of student, practices of differentiation as well as assimilation, and so on.

A part of what I’m trying to do is get them to acknowledge that broader implications are attached through social and cultural discourses to the clothes we wear, or the clothes others wear; that often the “messages” we think we are presenting about ourselves, about our concerns, are ambiguous, and ideologically loaded whether we are conscious of this or not; and that these messages are being conveyed along axes of often uneven power. For instance, when professors read their appearance as indicative of intellectual laziness, or when university staff recognize students by their sweats, and fellow workers by their absence. I’m also hoping to have them think consciously about the reasons they wear the clothes they do – that “comfort” and the desire to seem effortless, or alternately studious (part of a “I’ve been at the library all day” look), are not necessarily obvious values or qualities but are actively constructed and circulated by their everyday dress practices.

I still hate their sweatpants, though.

10 June 2008

STYLE ICON: Alice Bag

In 1977, Los Angelenos Alice Armandariz and Patricia Rainone formed The Bags, who went on to become an important (if brief-lived) fixture in the LA punk scene. What little footage I've seen of their live performances still sends shivers up my spine -- Alice is such an indomitable force in stiletto boots and torn t-shirts, blackened eyes and shock of hair (sometimes covered by a paper bag for the band's early performances), all sneer and prowl on stage. In still photographs, Alice is beautiful, tough, defiant and intense, whether she's wearing bondage pants or a '60s femme fatale black sheath dress. Women like Alice Bag were my style references for punk rock feminism when I was a suburban teenager dreaming of escape.

I bring her up because of the new exhibition Vexing: Female Voices from LA Punk at the Claremont Museum, at which Alice Bag performed for the exhibition's opening night gala. (Check out the Los Angeles Times article about the exhibition here.) Here's part of the exhibition's description:

The burgeoning punk rock music scene of the late 1970s and early 1980s in East Los Angeles provided an electrically charged, creative climate. This scene created an atmosphere where performance mixed with poetry, and visual culture was defined by an aesthetic and an attitude. Artists and musicians interfaced and blurred the lines of actions, documentation, photography, sound and style. Taking its name from the all-ages music club The Vex, once housed within East Los Angeles’ Self Help Graphics and Art, Vexing is an historical investigation of the women who were at the forefront of this movement of experimentation in music, art, culture and politics, while exploring their lasting legacies and contemporary practices. This documentary-style exhibition will include photo, video and audio archives of the era as well as studio work encompassing painting, installation, writings and performance.

I hope I can get to Los Angeles again (my girlfriend is a dedicated partisan to the early LA punk scene, and we somehow missed the exhibition when we were in town a few weeks ago) before the exhibition closes, but meanwhile, I'm inspired to try to incorporate Alice's amazing presence in the coming months. Check out the rest of her amazing photo gallery at her website. (And for the site --and posts-- that inspired this one, check out No Good For Me's own list of style icons.) (Mimi)

I bring her up because of the new exhibition Vexing: Female Voices from LA Punk at the Claremont Museum, at which Alice Bag performed for the exhibition's opening night gala. (Check out the Los Angeles Times article about the exhibition here.) Here's part of the exhibition's description:

The burgeoning punk rock music scene of the late 1970s and early 1980s in East Los Angeles provided an electrically charged, creative climate. This scene created an atmosphere where performance mixed with poetry, and visual culture was defined by an aesthetic and an attitude. Artists and musicians interfaced and blurred the lines of actions, documentation, photography, sound and style. Taking its name from the all-ages music club The Vex, once housed within East Los Angeles’ Self Help Graphics and Art, Vexing is an historical investigation of the women who were at the forefront of this movement of experimentation in music, art, culture and politics, while exploring their lasting legacies and contemporary practices. This documentary-style exhibition will include photo, video and audio archives of the era as well as studio work encompassing painting, installation, writings and performance.

I hope I can get to Los Angeles again (my girlfriend is a dedicated partisan to the early LA punk scene, and we somehow missed the exhibition when we were in town a few weeks ago) before the exhibition closes, but meanwhile, I'm inspired to try to incorporate Alice's amazing presence in the coming months. Check out the rest of her amazing photo gallery at her website. (And for the site --and posts-- that inspired this one, check out No Good For Me's own list of style icons.) (Mimi)

07 June 2008

Reason for Revival

I was recently invited to give a paper at the University of California, Irvine, for The Transnational/Transoceanic Networks: Histories and Cultures Project, sponsored by Women's Studies. My panel, called "Fashion, Consumer Cultures and Muslim Diasporas," also featured Reina Lewis, Artscom Centenary Professor of Fashion Studies at the London College of Fashion, University of the Arts, and Emma Tarlo, Lecturer in Anthropology at Goldsmiths, University of London and author of Clothing Matters: Dress and Identity in India (University of Chicago Press 1996), a monograph I teach all the time in my fashion course (my students love it).

It was great fun to present some of the work I've been doing over the last year or more on "the biopolitics of beauty," especially to an audience packed with feminist scholars whose work I totally adore (including one of my former advisors, eep!). Reina presented on some of the initial evidence from her new project on emerging Muslim lifestyle magazines, including Alef (Kuwait), Muslim Girl (US), Azizah, Emel (UK), and Pashion (Egypt), and focused on how the editors and stylists approach their fashion editorials (e.g., one made an editorial decision not to show their models' heads to exclude neither Muslim women who veil or those who don't, while another shows both covered and uncovered models) and the challenges they face with magazine production (e.g., getting product in the first place) and reader expectation. Emma also previewed new work, with photographs and interviews with cosmopolitan, college-educated British Muslim young women who choose the hijab, and the ways in which they manage and negotiate their visibly Muslim appearances. (I think her book, Visibly Muslim, is due out soonish.)

We spent all day talking about how "clothing matters" together (Reina and I had a very involved discussion about queer presentation), which inspired me to first, finally post (Minh-ha's been doing all the work so far), and second, vow to post on a regular basis. So stick around for more, hopefully. (Mimi)

It was great fun to present some of the work I've been doing over the last year or more on "the biopolitics of beauty," especially to an audience packed with feminist scholars whose work I totally adore (including one of my former advisors, eep!). Reina presented on some of the initial evidence from her new project on emerging Muslim lifestyle magazines, including Alef (Kuwait), Muslim Girl (US), Azizah, Emel (UK), and Pashion (Egypt), and focused on how the editors and stylists approach their fashion editorials (e.g., one made an editorial decision not to show their models' heads to exclude neither Muslim women who veil or those who don't, while another shows both covered and uncovered models) and the challenges they face with magazine production (e.g., getting product in the first place) and reader expectation. Emma also previewed new work, with photographs and interviews with cosmopolitan, college-educated British Muslim young women who choose the hijab, and the ways in which they manage and negotiate their visibly Muslim appearances. (I think her book, Visibly Muslim, is due out soonish.)

We spent all day talking about how "clothing matters" together (Reina and I had a very involved discussion about queer presentation), which inspired me to first, finally post (Minh-ha's been doing all the work so far), and second, vow to post on a regular basis. So stick around for more, hopefully. (Mimi)

FILM: Useless/Wu Yong

Thanks to Selvedge, I've stumbled across the 2007 documentary Useless/Wu Yong from award-winning Chinese director Jia Zhangke about the experimental work of Chinese fashion designer Ma Ke. The documentary follows the preparation and launch of her collection Useless in Paris, and also serves as a meditation on craft and industrial production under late capitalism. From the synopsis:

A hot and humid day in Canton. Amid the thunderous noise of sewing machines, women work quietly under fluorescent lamps in a garment factory. The clothes they make will soon be shipped to unknown customers. Likewise, the future of each face along the assembly line is blurred.

A wintry day in Paris. Chinese designer Ma Ke prepares her newly established brand “Wu Yong” (Useless) to be launched in a spectacular show. An anti-fashion designer, she abhors assembly lines. The trademark of her majestic line is based on first burying the clothes in dirt to allow nature and time to put the finishing touches on her work.

There's also a press kit you can download from the official site, which includes interviews with both the director and designer. Here, Zhangke talks about the many layers of his film:

[Ma Ke's] work went far beyond the image I had of fashion design; to my surprise, I found that her ‘Wu Yong’ collection made me reflect on China’s social realities, not to mention history, memory, consumerism, inter-personal relationships and the rise and fall of industrial production. At the same time, the idea of making her the subject of a film gave me the chance to look at a wide range of social levels as I followed the process from design to manufacture to exhibition in the garment industry.

I hope that we'll get to see this documentary soon -- I can't seem to find any information about screenings or DVD release.

A hot and humid day in Canton. Amid the thunderous noise of sewing machines, women work quietly under fluorescent lamps in a garment factory. The clothes they make will soon be shipped to unknown customers. Likewise, the future of each face along the assembly line is blurred.

A wintry day in Paris. Chinese designer Ma Ke prepares her newly established brand “Wu Yong” (Useless) to be launched in a spectacular show. An anti-fashion designer, she abhors assembly lines. The trademark of her majestic line is based on first burying the clothes in dirt to allow nature and time to put the finishing touches on her work.

There's also a press kit you can download from the official site, which includes interviews with both the director and designer. Here, Zhangke talks about the many layers of his film:

[Ma Ke's] work went far beyond the image I had of fashion design; to my surprise, I found that her ‘Wu Yong’ collection made me reflect on China’s social realities, not to mention history, memory, consumerism, inter-personal relationships and the rise and fall of industrial production. At the same time, the idea of making her the subject of a film gave me the chance to look at a wide range of social levels as I followed the process from design to manufacture to exhibition in the garment industry.

I hope that we'll get to see this documentary soon -- I can't seem to find any information about screenings or DVD release.

06 June 2008

Copy Cats and Cheap Chic

We all know about the raft of allegations and lawsuits for intellectual copyright infringement aimed at Forever 21, Top Shop, H&M, and other discount retailers. (Fashionista regularly features sharp-eyed notes about the proliferation of such copies.) Because these retailers replicate print patterns, dress styles, et cetera, major designers claim cheap manufacturing and mass distribution degrades the "originality" of their creative output.

This is, of course, the rehearsal of what Walter Benjamin called “the aura” in his essay, “The Work of Art in an Age of Mechanical Reproduction. This "aura," he argued, was first derived from art's original value in religious ceremonies and rituals, and later from the Renaissance's secularization of art as singular works of individual genius. This produced the notion of "art of art's sake," of art as transcendent and of the artist guided by a privileged insight into capital-T truth, in the 1800s, against the rapid industrialization and urbanization of "culture."

We can see this at work in claims by major designers against Forever 21 and its cheap cohort of retailers. At the same time, major designers buying vintage and copying these pieces include Jill Stuart, Anna Sui, Jean Paul Gautier, and of course Marc Jacobs, who is seen browsing vintage stores in New York City for just this purpose in his new documentary. Some of these same designers are part of copyright lawsuits against Forever 21 and other discount retailers – and a few are finding themselves at the other end of such lawsuits.

Famed Belgian deconstructionist designer Martin Margiela was recently dinged for only slightly, --very, very slightly-- modifying a copyrighted t-shirt design featuring an ominous sky full of thundering white horses and a barren mountain cliff. Reproduced on an asymmetrically draped and padded cotton shirt, and sold out at the designer’s Beverly Hills boutique, the almost exact image’s copyright belongs to British artist David Penfound, who sells reproduction rights to the painting for as much as one of Margiela’s shirts.

TOP: Margiela's version from the S/S 08 collection, BOTTOM: Penfound's original from a $20 t-shirt.

Margiela's representatives say the graphic is a "collage of nostalgic images compiled in-house." Nevermind for a moment that there is pretty much no "collage" effect at all in the copy. This invocation of nostalgia is telling because it suggests a fashion-backwardness, a temporal anomaly, brought forward into the future at the behest of the fashion-forward. This nostalgia for a certain set of images, however, is nonetheless contemporaneous; a particular aesthetic imagined to be still alive and, as many observers have noted, representative of a series of degraded cultural touchstones: “Midwestern gas station,” “trailer trash,” and “cheap and ugly souvenir.” (This chain of associations is no accident.) One fashion blog commentator wrote, “I picture the original on someone buying an extra-large order of nachos and a foot-long hot dog.“

These aesthetic judgments of the original design are called upon in both defenses and denunciations of Margiela. In the first, such judgments suggest that the original design was of such poor aesthetic quality that Margiela’s replication of the design only elevated something that was otherwise cultural detritus. Which is to say, Margiela’s transformation of the design (in the details and drape) can and should be regarded as the design’s alienation –not as isolation but as repudiation—of the original. In the second, such judgments argue that the original design is too ugly to redeem, too “cheesy” to rip off.

So what sort of aura is it when major designers copy cheap and derided --in no uncertain terms of economic and cultural capital— thrift store and vintage items? How are discourses of art and originality distributed unevenly, unequally, here? How do certain ideas about other peoples’ styles travel, and inform (or not!) the clothing options and choices for the consumers of these styles? How do these same ideas inform the clothing options and choices for consumers of these styles when they are “transformed” in other contexts – whether Urban Outfitters’s array of vintage reprints for the college crowd, or Martin Margiela’s vintage rip off for the wealthy?

Consider feminist media theorist Judith Williamson’s seminal essay, “No Woman Is an Island:” "It is currently 'in' for the young and well-fed to go around in torn rags, but not for tramps to do so. In other words, the appropriation of other people's dress is fashionable provided it is perfectly clear that you are, in fact, different from whoever would normally wear such clothes." Written in 1986, it seems this still applies.

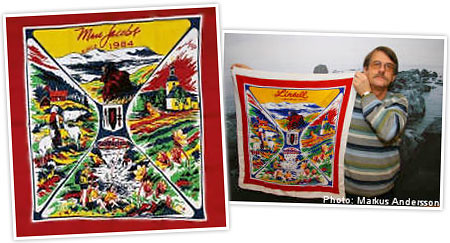

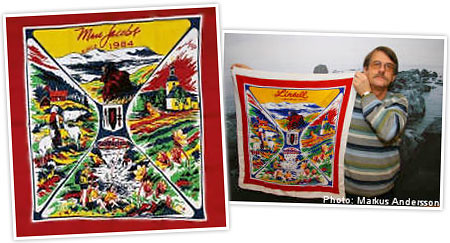

Meanwhile, 55 year-old Swede, Göran Olofsson, has been compensated an unknown amount for the scarf that Marc Jacobs blatantly plagiarized for Louis Vuitton. The scarf had been designed and created by Olofsson’s father Gosta in the 1950s as part of a line of tourist souvenirs for the Swedish small town of Linsell, and the print on Jacob's silk scarf was a near exact copy. (He replaced the name of the town with the tagline, "Marc Jacobs since 1984.") (Mimi)

This is, of course, the rehearsal of what Walter Benjamin called “the aura” in his essay, “The Work of Art in an Age of Mechanical Reproduction. This "aura," he argued, was first derived from art's original value in religious ceremonies and rituals, and later from the Renaissance's secularization of art as singular works of individual genius. This produced the notion of "art of art's sake," of art as transcendent and of the artist guided by a privileged insight into capital-T truth, in the 1800s, against the rapid industrialization and urbanization of "culture."

We can see this at work in claims by major designers against Forever 21 and its cheap cohort of retailers. At the same time, major designers buying vintage and copying these pieces include Jill Stuart, Anna Sui, Jean Paul Gautier, and of course Marc Jacobs, who is seen browsing vintage stores in New York City for just this purpose in his new documentary. Some of these same designers are part of copyright lawsuits against Forever 21 and other discount retailers – and a few are finding themselves at the other end of such lawsuits.

Famed Belgian deconstructionist designer Martin Margiela was recently dinged for only slightly, --very, very slightly-- modifying a copyrighted t-shirt design featuring an ominous sky full of thundering white horses and a barren mountain cliff. Reproduced on an asymmetrically draped and padded cotton shirt, and sold out at the designer’s Beverly Hills boutique, the almost exact image’s copyright belongs to British artist David Penfound, who sells reproduction rights to the painting for as much as one of Margiela’s shirts.

TOP: Margiela's version from the S/S 08 collection, BOTTOM: Penfound's original from a $20 t-shirt.

Margiela's representatives say the graphic is a "collage of nostalgic images compiled in-house." Nevermind for a moment that there is pretty much no "collage" effect at all in the copy. This invocation of nostalgia is telling because it suggests a fashion-backwardness, a temporal anomaly, brought forward into the future at the behest of the fashion-forward. This nostalgia for a certain set of images, however, is nonetheless contemporaneous; a particular aesthetic imagined to be still alive and, as many observers have noted, representative of a series of degraded cultural touchstones: “Midwestern gas station,” “trailer trash,” and “cheap and ugly souvenir.” (This chain of associations is no accident.) One fashion blog commentator wrote, “I picture the original on someone buying an extra-large order of nachos and a foot-long hot dog.“

These aesthetic judgments of the original design are called upon in both defenses and denunciations of Margiela. In the first, such judgments suggest that the original design was of such poor aesthetic quality that Margiela’s replication of the design only elevated something that was otherwise cultural detritus. Which is to say, Margiela’s transformation of the design (in the details and drape) can and should be regarded as the design’s alienation –not as isolation but as repudiation—of the original. In the second, such judgments argue that the original design is too ugly to redeem, too “cheesy” to rip off.

So what sort of aura is it when major designers copy cheap and derided --in no uncertain terms of economic and cultural capital— thrift store and vintage items? How are discourses of art and originality distributed unevenly, unequally, here? How do certain ideas about other peoples’ styles travel, and inform (or not!) the clothing options and choices for the consumers of these styles? How do these same ideas inform the clothing options and choices for consumers of these styles when they are “transformed” in other contexts – whether Urban Outfitters’s array of vintage reprints for the college crowd, or Martin Margiela’s vintage rip off for the wealthy?

Consider feminist media theorist Judith Williamson’s seminal essay, “No Woman Is an Island:” "It is currently 'in' for the young and well-fed to go around in torn rags, but not for tramps to do so. In other words, the appropriation of other people's dress is fashionable provided it is perfectly clear that you are, in fact, different from whoever would normally wear such clothes." Written in 1986, it seems this still applies.

Meanwhile, 55 year-old Swede, Göran Olofsson, has been compensated an unknown amount for the scarf that Marc Jacobs blatantly plagiarized for Louis Vuitton. The scarf had been designed and created by Olofsson’s father Gosta in the 1950s as part of a line of tourist souvenirs for the Swedish small town of Linsell, and the print on Jacob's silk scarf was a near exact copy. (He replaced the name of the town with the tagline, "Marc Jacobs since 1984.") (Mimi)

Labels:

copyright,

Forever 21,

lawsuit,

Marc Jacobs,

Martin Margiela,

theory

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)